The In-Season Training Manifesto

Chris Sinagoga |

Chris Sinagoga |  Monday, December 22, 2014 at 4:00PM

Monday, December 22, 2014 at 4:00PM by, Chris Sinagoga and Brian Hassler

Myintrotoletuknow

Basketball players will routinely take 500-1000 jump shots during practice sessions. We even brag about it. But the funny thing is nobody has ever taken 500-1000 shots in a game (not even Russell Westbrook). So if it’s never gonna happen in a game, then why do we practice it?

It’s because everything we do in practice is an exaggeration of reality.

We practice techniques, skills, plays, and scenarios over and over and over and over so that when the game finally comes, you are more likely to perform the right way.

The weight room is practice. The weight room is the lab. It’s the safest environment in all of athletics. Everything we do in the weight room needs to exaggerate the reality of our sports. We can reproduce and challenge positional demands, movement patterns, and training stimulus that we will see in our sport. We do this through a very formal approach we call strength and conditioning.

My background in strength and conditioning comes from an innovative lens that was introduced to me in 2005 by Brian Hassler (the co-author of this essay). That lens, of course, is CrossFit.

Throughout high school and college, CrossFit was integral in my development as an athlete. The routine was simple: CrossFit in the off-season, avoid the weight room at all costs during the season, then come back after the season to the unacceptable reality of Brian beating me in workouts. Unfortunately, he still brags about those glory days.

Then in 2009, through the suggestion of Brian, himself, I stopped being stupid and continued CrossFit during my basketball season. Only instead of the soul-crushing burners the main site prescribed on a daily basis, I did scaled “in-season” workouts. Throughout the course of my college basketball career, Brian and I had the opportunity to experiment with different programs, exercises, and mobility techniques that seemed to translate the most to the court. Since then, we’ve had hundreds of athletes as our test subjects.

This essay is meant to be a blueprint for coaches and athletes to begin the same process. It is not prescribing CrossFit or any other program. It is not a movement tutorial. It is not a lesson in anatomy. Rather, it gives you the foundation and understanding to perform a science experiment – and the test subjects are you and your team. There are three main ideas we want you to come out of here with:

- In-season training is mandatory

- Use yourself as a test dummy

- The strength coach, sports coach, and athletes need to be on the same page

Working out sucks, and is astronomically more boring than playing actual sports. If it were up to me, you could take our Fundamentals, do the CrossFit Total, Elizabeth, and Murph, and you would be set for life. Unfortunately, biology doesn’t quite work like that. So might as well make the most out of the time spent in the weight room so it translates to the fun stuff. Hopefully in doing so you will discover what kind of in-season training is minimal, optimal, and realistic.

So without further adieu, we present The In-Season Training Manifesto.

Position

Most every coach knows that there is weight-room strong and there is game-strong. 40-yard dash speed, and game-speed. The I Can’t Bench My Bodyweight kid that still destroys people on the field has coaches second-guessing everything about their program. Or sometimes they just ride it off as being a case of lucky genetics. While I don’t think there will ever be a definite answer, it’s become certain that great performance in the weight room does not always translate onto the field. Why is that? In my experience, most of the issues come down to the misunderstanding of one single term:

Strength.

Often confused with “big,” strength is something all coaches want their athletes to gain – whether it’s brute strength for a lineman or strength endurance for a Cross Country runner. Traditionally, this strength is developed by going to the weight room and lifting weights. And how do athletes and coaches know there is a strength gain? They add a pound to the bar and see if the repetition can be completed. It’s the most simple method of tracking progress.

The problem is we do this so often that we lose sight of the original purpose. Instead of doing a movement to serve our bodies, we do the movement to serve the weight we add to the bar. In the words of world-class coach Carl Paoli, we should strive to be movement-strong, not numbers-strong.

Spot me bro

Spot me bro

I view strength simply as your ability to hold a stable position. The more movements you’re able to maintain stability, the stronger you are. In the world of athletics, this definition is consistent. Can you maintain a stable midline while blocking that rabid monster trying to assassinate the quarterback? Can you finish around the rim while you are in the air and defenders are hacking you from every angle? Can your hips, knees, and ankles support your decaying body as you sludge through a 5k Cross Country race? If we can accept that interpretation of strength, the question then becomes: What exactly is a stable position?

Kelly Starrett does an incredibly precise job of defining and illustrating stable positions in his best-selling book Becoming a Supple Leopard. But for the purpose of this article, a stable position is basically staying as close to our anatomical stance as possible. It’s also important to remember that your safest position is always your strongest position. It may take a while to get used to it, but long-term it is the way to go.

Let’s take the feet for example. We know that toes-pointed-forward is an anatomically stable position for the foot. From there, all of the muscles, bones, and tendons are aligned and are in the best position to move. On the contrary, we also know that feet turned out (or duck feet) promotes a collapsed ankle – which also unwinds the ligaments in the knee and creates instability at the hip. Over time this is the recipe for plantar fasciitis, shin splints, ACL and meniscus injuries, hip impingement, low back pain, and many non-contact injuries that happen in sports. So the fix? Duh, keep your feet forward.

Easy enough, but habits are difficult to break – especially when they are built up for years and encouraged by things like sitting for seven 7 hours a day at school or work. And more importantly, you have better things to worry about during a basketball game than what your feet look like while you are trying to grab a rebound. Once we venture into the world of athletics, there are numerous outside stressors that take our attention away from position – which means we need a place to practice it.

So here’s something to consider: what setting do you think would be the easiest to keep your feet in a good position? 1) Jumping rope. 2) Olympic lifts. 3) Spiking the ball at the volleyball net.

Obviously the answer is doing jump ropes. We have both feet planted, aren’t jumping very high, using minimal weight, and don’t have to think about bar path or where to place the hit. Regardless of the difficulty, all three options contain the same fundamental jumping/landing movement pattern, and therefore the same jumping/landing principles must apply. Once you develop good positions while jumping rope, test out the same thing doing a clean or snatch. With enough repetitions, those habits will carry over to how you land on the volleyball court.

What makes sports even more challenging (from an anatomical perspective) is the fact that we spend a lot of time unbalanced with more weight on one side of our body than the other (running, changing direction, throwing, kicking). This unilateral loading makes it even more difficult to maintain a stable position. This is where true strength comes into play and can be crucial in preventing injury.

Matt Morrow - exceedingly handsome but unable to keep good position in a pistol

Matt Morrow - exceedingly handsome but unable to keep good position in a pistol

If strength is your ability to hold a stable position, then mobility is your capacity to get into that position. If lack of mobility is the issue, we can assign mobility drills to increase range of motion in a particular shape. Much like movement practice, our goal with mobility is to exaggerate reality. We would like to have more range of motion than we think would need during sport so lack of mobility would never be an issue. But it is also important to remember that new range of motion is weak range of motion – so it’s best to strengthen and reinforce those shapes and positions by going through formal movement progressions in the safe environment of the weight room before we go onto the field or court.

Movement

Think of the weight room as an English classroom. It is a setting where you are taught the very basics of a language in a formal, progressive manner. Then once you learn the foundations of that language, you apply that to whatever setting you find yourself in. Only in this instance, the language is movement.

Here’s an example: when teaching an athlete the general skill of pushing, a coach would take a newbie through a formal progression in the order of:

The athlete then takes that general skill and applies it to whatever their sport, or life, may require. Understanding the relationship of the movements also gives the coach easy solutions to help a struggling athlete as well as challenge an advanced athlete. If an athlete can’t keep position in a dip, then we backtrack and address the movement fault at the push-up level. If they look good, then we progress onward.

But for whatever reason, the language seems to abruptly change when transitioning from weight room talk to on-the-field talk. Coaches and athletes often overlook the connection between the movements in the weight room to the movements in their sport. If we were to continue the push-up mechanic further in the movement spectrum, it would look something like this:

The order is not exact, or even important. But what is important is to understand that all of those sport-specific skills derive from the fundamental principles found in the push-up; and that missing a performance point in the push-up will affect everything that comes after it. Better push-ups = better volleyball. Even though there is a long distance between the two, the connection is still there. I like to think about these relationships using a pyramid. The diagram below should be read from the bottom-up and movements listed at each level are examples of movements found there, not the only ones.

On the bottom, we have the foundational movements that athletes learn which all other movements derive from. Practice at this level develops strength in simple movement. This is the easiest place to address movement faults seen at high levels, although an experienced coach can spot the same fault at this level.

Next, we have more advanced progressions of the foundational movements. Movements here involve adding skill and accuracy while taking away connection from the ground or a stable surface. Practice at this level develops strength in dynamic movement. This category is interesting because even though it allows for greater power output, it becomes more difficult to maintain good position. This is typically the last level where position is addressed. Anything further upstream and the skill of the movement is usually emphasized.

Lastly we have running – which I see as the most technical skill we do in strength and conditioning and in a class by itself. Every movement principle seen in the lower levels funnels into the foundational positions of running. Midline stability, landing mechanics, hip flexion/extension, and shoulder position are all important components of running. However, due to the extremely high amount of reps that occur (approx. 340 steps in a 400-meter run alone) and speed which the athlete is moving, it’s almost impossible to concentrate on position. Instead, the athlete should be thinking about running technique. The athlete will rely on the positions enforced and practiced during the two previous levels to carry over to running. If those positions are good, they will carry over. If they are bad, they will also carry over.

...........

But once we venture out into the world of athletics, we are changing the game. Running becomes one of, if not the foundational skill that connects almost every main sport we see on the high school level. Everything gets harder after that (which is why the slogan Our sport is your sport's punishment is really nothing to be proud of). So when we move up the ladder past the weight room, we see running on the bottom of the pyramid that all the skills in sports then branch out from. And in the sport of running, race strategy (along with running technique) takes even more attention away from position due to the introduction of outside competition.

At the second level, we have reaction-based movements. These movements involve the same running and jumping mechanics seen in the weight room, only there is a reaction component involved. This would be man-to-man coverage for a cornerback, stealing a base, shuffling on defense. In this scenario, the athlete is not concentrating on either the position or skill of the movement. Their attention is paid to whatever it is that caused them to react – whether that’s the ball or the opponent.

Finally, we have tactical-based movements. At this level, all of the principles mentioned in the previous layers (position, skill, accuracy, reaction) come into play, only these require a great deal of hand-eye or foot-eye coordination. The best athletes in the world are usually naturally gifted in this area – which is a topic for another discussion altogether. This level is mainly sport-specific skills that Brian likes to call "Tactical Modifiers" because they accentuate the ability of the sports coach and can modify his gameplan. But as expected, specific anatomical position is nearly impossible to control at this level. Whatever habits practiced in the weight room and daily movement (good or bad) will be on display.

Aaron Sexton - good foot position reinforced through endless box jumps, burpees, and cleans

Aaron Sexton - good foot position reinforced through endless box jumps, burpees, and cleans

The most important thing when teaching movement at any level is setting a standard. That way you have a point of reference. You can either emphasize the timing/skill of the movement, the local/global positions that occur, or the metabolic response. For advanced athletes, you can demand all three at times. Then once you decide, set a standard that must be matched in order for the rep to count. For instance, maintaining hook grip on the pull-up bar sets a standard to ensure a stable shoulder position, whereas being able to keep a butterfly kipping motion to challenge coordination would emphasize skill of the movement, and completing 20 pull-ups every minute for 5 minutes would be a metabolic standard. A small deviation from the standard is a mistake and a large deviation is an error. A mistake might be corrected on the fly, where an error may cause the coach to stop the athlete and discuss. This is consistent through all levels of the movement pyramids.

A well-rounded strength and conditioning program primes the most fundamental layers of the movement patterns you see in your sport. No matter how advanced you are as an athlete, the best way to improve is to master the basics. And in-season training does just that. What you see on the field, court, or track are very advanced progressions of what is happening in the weight room. They are connected through the same joints, muscles, tissues, and neurological pathways across that movement spectrum. If you can’t find connection then your training is compromised.

So what happens if we take that foundation away during the most important time of the year? You’re about to find out as I pass the baton to Brian.

Purpose

Option, Veer, Power I, or Pro-style?

The question you may be asking yourselves right now is what do the four things above have to do with in-season training. If you aren't a football coach then you may have even more questions. Before continuing, I have some questions for those reading this.

- Is in-season training an option for your athletes? Is it mandatory or optional?

- Do you have the time, commitment, and resources to run a strength program?

- What are those resources? (facilities, personnel, time, etc..)

- Who is deciding what the athletes are doing?

- Are the athletes being veered toward or away from the weight room?

There is a saying, “what I allow, is what I encourage”. If we allow our athletes to be any less disciplined and regimented in their time in the weight room than we do on the field then we are encouraging a less than optimal approach. The power of I is just as important, do not underestimate it. With the resources available to most athletic programs there is no reason to not employ a pro style in regards to the training of our athletes. 4 factors that go into the pro style are programming, progression, promotion and protection. It starts with proper programming with a progressive overload. Then promoting the benefits of the program. A simple plan that the athletes believe in is just as good as the most sophisticated plan that they don't believe in. Finally, we have to protect the athlete. Looking at the big picture that means creating stronger athletes, because increasing strength will enlarge the “cup” for all other athletic abilities. On a smaller more specific scale that can look like strengthening the neck to protect against concussions or fixing landing/deceleration techniques to protect the knee.

Key point: Have a program, continue to progress , promote the plan and protect your athletes.

Blocking movement for quality landing while adding a minor tactical aspect (holding a football)

Blocking movement for quality landing while adding a minor tactical aspect (holding a football)

Program: The Off-Season to be continued...

The In-Season is the focus of this article but before that can be addressed you need to have a point from which to continue and the methods to achieve your goals and desired adaptations. There are many viable options such as the Tier System, 5-3-1, Triphasic, Bigger Faster Stronger to name a few and I will also provide my own program template at the end of the article. The key though is to determine what adaptation we are trying to get out of our athlete; Hypertrophy, structural integrity, strength or power, and the mode to accomplish that; repetitive, dynamic or max effort.

Hypertrophy/Structural Integrity via repetitive effort: This should be the focus for a few of the younger undersized athletes that aren't seeing significant playing time. Also for 1st team athletes with a large amount of uni-lateral workload or anyone post-injury e.g., the quarterback, right and left tackles, or an athlete returning from an ankle sprain; there will be some structural integrity work necessary. Repetitions from 8-20, 60-75 percent 1RM.

Strength via (sub) max effort: The no. 1 priority whether in season or not for the majority of our athletes. A slight shift in the terminology to a sub-maximal effort during training should be considered. The training age of most high school athletes will not allow for true max effort training because of degradation of form and lack of experience. Sub maximal effort will allow for a closer control on form and form breakdowns while still achieving the strength increases desired by the staff. Repetitions 1-6, 80 percent and above of 1RM.

Power via dynamic effort: Reserved for athletes that have a training age of +1 year e.g., junior or senior athlete, that has obtained a baseline of strength and movement experience to perform more dynamically challenging versions of exercises. Repetitions 3-6, 30-80 percent of 1RM. Speed of movement is more important than the weight of the movement.

Key point: If the program doesn't stop, neither do the adaptations. In-season training is a vital part of the total package.

Check your progressions

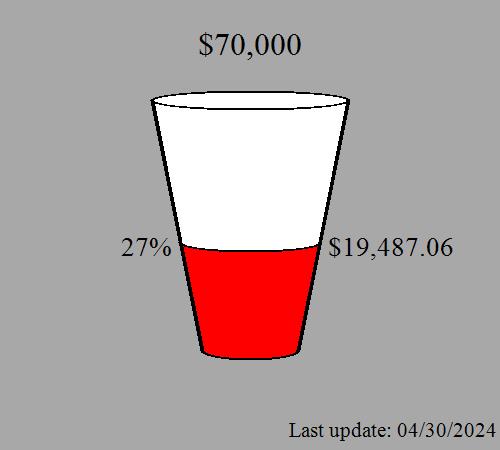

The strength of the athlete is built in the off-season with the in-season often used to “maintain” those gains. This is outdated thinking and less than optimal for the athlete from a short term and long term prospective. The short term would be the competitive season from that first two a day in August until the end of the season hopefully after Thanksgiving. The strength potential of the athlete is what they arrive to camp with. The minute that first whistle blows though the athlete will encounter a variety of different stresses that will impact his strength potential. Those stresses could be the type of offense, type of defense, weather, starter vs. sub, position, 2 way player, length of practice, intensity of practice, number of impacts, game day, school and life. The difference between the strength potential and the stress is the strength realization. For instance two weeks into the season after your first live scrimmage against another opponent the equation may look like this:

Strength potential 100% – stress impact 10% = strength realization 90%.

This decrease in strength will only continue as the season and the stresses increase unless there is a continual push to increase the strength potential through the in-season program. The question I often ask is why do we seek improvement on the field but maintenance on one of the key attributes of athletic ability. The word strength can easily be replaced with power. Do we not want powerful athletes at the end of the season? Then the training program must supplement that desire.

From a long term prospective many athletes play multiple sports (all though that is diminishing) and even though they are dedicated during the summer program they are often not training during other sporting seasons. This is where a solid program that can easily transition between “off” and “in” season athletes and focuses on some of the basic athletic abilities that I mentioned above such as strength and power can be useful and thus effectively communicated and shared with other coaches to get them on the same page regarding the long term athletic development of the athletes.

The biggest issue that I have encountered is not the program itself but the tracking of the program. The eye test is great but without numbers we are just guessing. Stats carry a lot of weight in football, win/lose record, points per game, points against, passing yards, rushing yards, turnovers, yards after catch. They should carry the same weight in the strength and conditioning program. This does not mean tracking every 2.5 LB plate the athlete lifts but there should be some form of record keeping based around qualities you deem important.

Strength: upper body (bench press), lower body (squat), total body (deadlift) *1RM or multiple RM

Power: overhead medicine ball toss, vertical or broad jump, olympic lifts and their variations

Acceleration: 10 yard sprint

Speed: 40 yard sprint

Agility: T-test, 5-10-5 shuttle run, 3 cone drill, Illinois agility test

Work capacity: repeat sprint test, repeat 30 yard shuttle run, etc…

Aerobic: mile time trial, 20-40-60 continuous shuttle run (5x for 1200 meter total distance)

Key point: The majority of the tests above will give you baselines of where your athletes are at from off-season to off-season, while continued progression of a few key lifts will help guide and narrow the focus during the in-season.

Seeking a Promotion: PT vs TP

This is not the old school coach’s homecoming week speech about choosing PT or TP. I am referring to a differing approach involving 3 elements of the athlete’s practice time: physical, technical, and tactical preparedness. Physical preparedness would involve any strength and conditioning. Technical preparedness covers any individual skill as it pertains to the sport such as a QB working on his 5 step drop, a WR running routes, or a defensive end working on a rush move these are often worked on during individual drills or indy’s. Tactical preparedness deals with any formations or adjustments both offensively and defensively. A player’s perspective may include reads that a defense player might have to make or audibles that are called, these are often worked on and adjusted during team offense and defense. There is a physical impact from all 3 components that does need to be accounted for but that can be done on an individual player by player basis.

In the off-season and if we reference the inverse pyramids from the above portion the majority of the time should be spent in physical preparation starting from the base with strength in movements, strength in dynamic movements, and running throughout the winter, spring and summer program. A portion has to be accounted for technical (4 man workouts, individual instruction and or camps) and tactical (7 on 7, team camp) preparation but the majority will be spent on physically preparing your athletes for the rigors of the game. This is not set in stone because some physically gifted athletes may need more of a technical focus.

In-season the script is flipped. The majority of the time is spent with technical and tactical preparation, but we cannot exclude the physical component. Again if we reference the inverse pyramid, you can see that the majority of the sport season is spent above the reaction based movement line and in a tactical/technical setting, and the foundation becomes less stable when most of the physical training is based off of running and conditioning, (gassers, half or full, etc...) By adding in the level 1 basic movements of strength we do not allow the foundation to crumble. In fact with proper programming we can continue to enhance the athletic base.

Adding a reaction component to dynamic level movement

Recap:

Off-season: Physical (injury rehab, winter to summer workouts) + Technical/Tactical (4 man workouts, 7 on 7, Team Camps, Individual Camps)

In-season: Tactical/Technical (Skills/Drills, Team O/D, Film, scrimmages and games) + Physical (Training Room, Conditioning and Weight Room)

Key point: Football season is technically and tactically based, but promotion within of a physical culture is necessary to optimally prepare the athlete.

Protection Breakdown: Repetition vs Repetitive

Repetitions are an important component of mastering any skill. The beauty of the off-season is that the variety of repetitions can cover a greater spectrum than what is faced during the sport season. The sport specific nature of repetitions and the number accumulated between players during the season can vary greatly between different level athletes and can lead to repetitive traumas.

Scenario A: two-way starting tailback/strong safety that gets 20-25 high impact carries/touches a game with over 50 snaps from defense and offense. That is potentially 100 repetitions per game on the body. Add in first team repetitions that could range from 20-40 impacts per practice per side of the ball. The player will see conservatively over 300 repetitions per week.

Scenario B: one-way starting offensive lineman playing a tackle position. He will average 50-60 plays per game. First team repetitions during practice could put him well over 200 plays per week.

Scenario C: Underclassmen 2nd team quarterback. Limited, if any snaps during the game. Mostly scout team repetitions during practice and less than 50 percent of 1st team snaps. Limited contact of QBs.

The commonality between the first two players is that throughout the week they will face a repetitive stress with impact that will accumulate unless accounted for. The accessory work for these athletes can address diminishing mobility, accentuating stability, soft tissue management, and overall structural integrity.

Key point: The in-season program must address any possible “protection” breakdown that your athletes will encounter.

Chris and Brian. Post in-season training session, 2010

Chris and Brian. Post in-season training session, 2010

BONUS: Programming Notes from Brian

There is a saying by strength coach Eric Cressey, “if you are fast, train strength. If you are strong, train speed. If you are neither stop thinking so much and just train”.

The basis of this program is APRE – Auto-regulatory Progressive Resistance Exercise. This provides the strength coach and the athlete with a guideline for when to increase or decrease the resistance on specific lifts the coach is tracking while fitting within the desired adaptation.

For example: An athlete on a 10RM APRE program on a day with the focus on upper body strength with a 10RM of 200 lbs in the bench press does the following for the bench press

1st set 100 lbs for 12 reps (12 reps @ 50% of 10RM)

2nd set 150 lbs for 10 reps (10 reps @ 75% of 10RM)

3rd set 200 lbs for max reps, athlete gets 13 reps. Weight increased 5 lbs for set 4

4th set 205 lbs for max reps, athlete gets 12 reps. Starting APRE weight next week is adjusted up to 210.

Two Days a Week Total Body Program

Day 1 Total Body Strength + structural deficiencies (SD) emphasis

Warm-up: Tissue work, Corrective Mobility, Dynamic Movement Prep

1A) Upper body push: Bench Press 6RM APRE (refer to notes above)

1B) PVC Seated Thoracic Torso Twist: 3x20 reps (SD)

2A) Lower body hinge: Double over Deadlift 4x3 reps (only concentric portion, drop during eccentric)

2B) lacrosse ball hip capsule smash 4x30/30 (30 secs per side) (SD)

3A) Upper body pull: 1 arm DB row 3x8/8

3B) Alternating Spiderman 3x5/5 (SD)

4A) DB Farmers walk + DB shrug 3x 40 yards + 8 shrugs

4B) Partner Hamstrings Stretch (contract/relax) 3 sets x 30/30 (SD)

Day 2 Total Body Power and Structural Integrity (SI)

1A) Total Body Explosive: Hang Power Clean 3RM APRE

1B) Squat Jump 4 sets x 3-5 reps (Jumping/Landing Mechanics) (SI)

2A) DB or KB Front Squat w/ 2 sec pause in bottom 5 sets x 5 reps

2B) Back Extension 3x10 reps (SI)

3A) DB Landmine press 3 sets x 8/8 reps

3B) Band pull-apart 3 sets x 15 reps (SI)

4A) Glute Bridge 3 sets x 15 reps (SI)

4B) Plank Complex (Side-Prone-Side) 3 sets x 45 secs (15 secs per)

Reader Comments (16)

Reminds me of the Lions...an average first half with a solid second half for the win.

This is so cool! Some stuff I had to read a couple of times to grasp the meaning, but this is awesome. When I train during in season, I never understood the importance of it. I just did it because I wanted to, but this has really changed my perspective of in season training. I have noticed myself tending to focus on the numbers I put on the white board way too much compared to focusing on my skill progression and relating what I learn in the gym to my sport and real life situations.

Hey Brian, this kind of reminds me of the Lions of the early 2000's. Great in the first half, then they blow the lead in the second.

And glad you found it helpful Bromm. I'm sure we'll discuss further

THERE ARE ACTUALLY PYRAMIDS. MY GOD.

Really cool read though. The quality of the writing on this site is unreal.

Jacob, unfortunately it wasn't until after I finished this that the great Matt Morrow enlightened me to the realization that before running, before box jumps, before push-ups, the base of all athletic gainz is the simple bicep curl. Handsome and smart.

Bicep curl is underrated and often maligned. I forgot to mention that off-season always must include a swole lot of curls. As the Russians used to say the only race that matters is the Arms race.

On another note, I must add a caveat. The tables that I used are taken from Bryan Mann (which was taken from Mel Siff and Verkoshanky in Supertraining). I have personally modify the Table 1. to include an increase in volume. Typically it revolves around a 4 week cycle.

1st week set 5 is a 10% decrease for whatever RM routine you are currently in i.e. 6RM = 6 reps @ 10% less

2nd week set 5 is another 10% decrease but I add a 6th sets i.e. 6RM = 6 reps of 2 sets w/ 10% less

3rd week set 5 is a 5% decrease for whatever RM routine you are currently in.

4th week set 5 is a 5% increase w/ the reps of whatever the NEXT RM routine is. For instance if you were transitioning from a 6RM to 3RM you would do your 5% increase for 1 set of 3 reps.

I find that this gives a bit more volume (or practice if it is the 10 RM) and places you in that higher intensity for 3 sets instead of 2.

One thing that Chris and I discussed is that during the season you will mostly be above the Reaction Based Movement Line that he references in his Inverse Pyramid. What is missing though is Strength or Strength in Movement that is found on the base of the pyramid.

Really nice job on this. A lot of what Brian said seems like what most strength coaches know but really take for granted. I don't see a lot of teams thinking about practicing positions or quality of movements much at all, and I think that "Protection of Athletes" has to be a priority in order for the program to be successful long-term. I know certain rowing and cross country/track coaches that could really use this article....

The first couple paragraphs were pretty solid, definitely stuff I’ve heard before. Russell Westbrook is one of the best examples I’ve ever heard from you haha.

I was wondering if you could elaborate a little more on when you started your in-season training in CrossFIt. Just kind of how you figured out what was good for you personally while working out in-season, and how you determine a program for an athlete in season. (How to use yourself as a test tummy) Cause I know a lot of times we personalize when we do one-on-ones, Amy, Ryan and I definitely had different preferences for game day/practice day workouts.

“I can’t bench my bodyweight kid,” - Mr. Durant?

I liked the distinction between big and strong. Some of the smallest people I know are also the strongest (see Air Canada).

Matt Morrow- I gotta give you some props for smiling during that pistol.

I really really like the Great Pyramids. I think this displays pretty deep knowledge of a topic- that you can take something complicated like movement and relate sport specific movement to fundamental movement in something as simple (for the concept) as two pyramids. This is something, with a little bit of tweaking- cause after all new range of motion is weak range of motion- it should be something that is painted on the wall in here. We’ve been familiar with the simple movement/dynamic movement concepts for a little bit, in terms of category 1, 2, and 3 stuff. I think the addition of reaction-based movements and tactical movements kinda change the game. I believe credit is to be given to Brian on these names/ideas if I remember correctly Chris? I’ve never seen so many movements categorized so efficiently- there is NOTHING that doesn’t fall into either of these categories.

I actually would like to hear more of your thoughts on tactical-based movements and how a lot of world-class athletes are highly skilled in them. Do you think that if foundational principles were applied then their tactical-based movement skill would increase? Or would these athletes just keep doing what they’re doing- albeit in a safer manner now that they know about feet straight/midline stabilization stuff? Or would their tactical skill decrease because now they’re focusing on that foundational stuff (again this idea of new range of motion being weak range of motion).

Nice transition to Brian’s part. 1. For the content. These two sentences rock, “If you can’t find connection then your training is compromised.

So what happens if we take that foundation away during the most important time of the year?”

Now unto Brian’s part. Brian, I’m not gonna lie this was a little hard for me to understand because I’m not really versed in weight room speak- only CrossFit. Which I know probably made you cringe haha.

I agree with your key points. Simple as that. I don’t know if I agree with the order though. I think I’d go with mashing program and protect together as the first point. You need a protective program at our level. Stealing from Chris who stole from Jeff Martin, “We want our kids to be able to participate in the Masters.” I’d like to see Lauren Higgins be safe and succeed in her college basketball career, and still be able to perform high skill movements and have her in the advanced mommy session. And still be kicking ass.

I like the idea of stress impact and the fact that a season will wear on athlete. It’s like in-season training is taking the car in to get the oil changed before your transmission falls out in the middle of the road cause of neglect.

Chris I’m sorry- but I think this was my favorite sentence in the entire article and I think it’s what summed up why we do what we do. And why you can’t stop doing it. Tyler Jabara. “By adding in the level 1 basic movements of strength we do not allow the foundation to crumble.”

In summary, thanks for the article guys. One of the best pieces on the website in a while, should be added to mandatory reading. Also Brian you should quit your job at Foley and come back and do your thing (boss Chris around and program).

Love this! A lot of great info in here and I will definitely need to read this several times!

Now, let me take you to a world where "sport" is called work. All of this still applies, and maybe even more so, when your "sport" has you sitting on your butt all day. When "off-season" is all damn year, the strength and stability goes to hell very quickly. This is one of the reasons that CrossFit is not only for the athlete but a program of elite fitness for everybody. At any point in one's life you may need to lift, run, or jump in a unilateral way and that can lead to injuries. My pyramid:

------------------ ----------------

\ / \ /

\ / \ /

\ / \ /

\ / \ /

\ / \ /

\ / \ /

\ / \ /

V V

is a desk. We old people need to keep moving because it's a really long off-season. Longer than basketball's season, longer than baseball's season, and even longer than the World Cup playoffs. That's why I do CrossFit -- for the long run.

Murley,

I think the problem you find at smaller schools is that one person is asked to do multiple jobs (trust me I know!) or they are doing a job because there isn't even a position i.e. Cross country coach doing the strength programming. Worst case they don't even offer a strength component.

Also I still think especially with Endurance sports there is a prevailing more is better one size fits all approach. A lot of the impact from lydiard and his long slow distance to build the aerobic base. Some athletes can handle that high volume work (look at rich froning, he may be the king of high volume in CrossFit terms) but many others simply cannot.

Also I like your take on the protection component. I think this could be something expanded into another article: A macro long term approach vs a micro in season approach. I think it could follow a gpp (general protection prep) to a spp (specific protection prep) during in-season stresses.

Emma,

I think you underestimate your knowledge...because really everything is terminology.

Hypertrophy or Swole aka Lynne

Strength aka CrossFit Total

Power aka Olympic Lifts

But all in all it is just terminology. So you can call it what you want but again it comes down to adaptation. The only thing that I would throw shade on with regard to CrossFit is that I think they spend a majority of their time hitting energy systems that may not be conducive to many of the power driven sport.

That being said, I have shifted and placed more emphasis on strength but that doesn't always translate to better sporting ability either. The saying "look like tarzan, play like jane" would ring true there. But if we narrow strength down to the level 1 of strength in movement and hammer those movements with the goal of progressively overloading them then I think we would see some real improvement in the younger athletes.

A book I would recommend to you and Murley is called Power Positions by Andrea Hudy. She is the strength coach for the Kansas Jayhawks men's basketball team and has also worked with the U-Conn programs also.

Ok Em, here I go:

I originally had a lot more in the intro about how I started. But I took it out. Anyways, my memory is foggy but I think I started in 2009 when CrossFit Football came about in the spring. I kept up with the site because Brian would do those WODs sometimes even though I still followed main site. When the Fall rolled around I noticed that they had in-season versions of their workouts. With the help of Brian, I did those all Fall and Winter (sophomore season) then transitioned back to main site after the season.

I don't remember if it was the next season (junior) or the one after that (senior) when I noticed that the transition from CF Football to main site was brutal because they excluded many lifts like kipping pull-ups and full cleans and snatches. Actually, I think it was my senior year when I decided to test out keeping with main site but scaling on my own. I was getting benched anyway to I figured "What the hell, might as well try it". Since then, I've stuck with scaling main site on my own. I think it's important to stay fresh with ALL of the movements during the season and just scale the volume or loads as needed.

I should also note that my junior year is when I started to workout on gamedays. I noticed that I would tend to get more sore the day after a workout than a day of. So I rested the day before a game and hit a decent workout the day of. I also learned that back squat, deadlift, and push press were the only things that I couldn't really do on gameday because they would make me sore. And situps of course. I tested everything else out and they proved to be fine. I always felt a lot better during games if I did a workout earlier in the day. I encourage everyone to test out the same. Don't be afraid to overdue it. I overdid it on gameday a few times but I learned and it was never the point where it costed our team the game.

As for the big and strong thing, I said that from experience as well - from my senior year in high school and junior/senior year in college. I was a "small" guard but I felt like I was stronger than just about every guard and small forward I played against. Even with The Family or D1 guys I still felt like I had a physical advantage. There were always exceptions (Marcus Hopkins on my Marygrove team was a bowling ball and MUCH stronger than I was. But that was his genetic build. For me to get that strong I would have to take a drastic cut in speed and quickness).

On to the pyramids. It started with Track is Like. I wrote down exactly how I felt with zero revision - it might as well have been an Untitled/Unedited Rant...if not for the great title. But after I wrote it, I made myself explain it to myself, if that makes sense. I really contradicted myself a lot in there even though it made sense to me. So in my head I tried to explain everything out. And it was then I realized that running is not always running. It was actually Dr. Romanov's student/teacher frame concept that helped me. In the frame of the weight room, running requires the most amount of skill and practice. In the frame of sports that matter, running (or track/cross country) requires by far the least skill. And I saw it like two pyramids. But then I put in on hold for the entire Summer.

In November, I sat down and revisited the pyramids I was thinking about. I remember being at the gym writing them out and starting with a rough copy. Then I tried to explain to myself why I thought running in sports was so much harder. Then I realized it was not because of change of shape, more range of motion, or faster movement. All of those factors came AFTER one single thing: reaction. So after more tweaking I sat down with Brian about a week and a half ago to discuss the Great Pyramids. At this point, everything was written for TISTM except the the part after the pyramids. I showed him that the line above Running category in sports was a reaction line. But I didn't know how to categorize the movements above. Then he suggested "Reaction-based movements." As simple as that was, it was a light bulb for whatever reason. Then we spent the rest of the time trying to figure out what to call the top layer. When I was walking home from our meeting, I texted him Tactical-based movements because of what he explained to me about his Technical/Tactical part. I thought it fit into his stuff.

I agree that it's not finished yet. But most of it is there. I need to understand why I think jumping is a bottom-level skill even though it's Category 2 according to Kelly. I also keep flipping between the ideas of:

"Kelly's movement hierarchy system is great. No need to reinvent the wheel."

and

"But we have Fundamentals."

Lastly, my thoughts on Tactical-based movements:

Again, I would like to use myself as an example. I felt like I was a pretty naturally gifted for a white guy. You name it, I could do it very well: sprint, run distance, jump high, jump far, dribble, shoot, catching passes, swing a baseball bat, throw far (baseball or football). In the frame of local high school sports, I feel like I was the best overall athlete in the area during my time and I haven't seen one since I left. I also had a teammate by the name of Clifton Powell who was black and had the same well-rounded abilities I had, only slightly better in each category except running distance. I had a better long jump than him and could dribble and shoot a little better, but that's only because I practiced more.

When he transferred in from St. Clement, it was my sophomore year of High School and I just started CrossFit. That year, he was much better than me in everything. Then I did CrossFit and he didn't and I closed the gap - so much so that in my honest mind I may have passed him up by a little by the time we were Seniors. I could shoot with the same range as him. I could jump as high (or very, very close), we could both throw the football 60 yards, and I closed the gap in sprinting and expanded the gap in distance running.

My point being is that I kind of see the two of us as the Kavanaugh twins. So it was like an experiment in my eyes. One person routinely worked on foundational movements and one did not. I also found that since I culd do everything at the top layer of the pyramid, things like kipping, ring dips, cleans, and such came fairly easy to me. And Clifton did CrossFit for about a month and the stuff came easy for his as well. This is precisely why I am "teaching" the preschoolers the way I am.

This, of course, is all from my biased perspective. I would be very interested to hear Brian's take on the matter, as he knew me before I did CrossFit and was there to witness Clifton and I go through high school.

Looking at the comment about jumping, I think you should look at landing and the mechanics associated with that as a basic movement or a bottom level skill and then jumping would be a high skill because you have connection in landing while in jumping you are removing connection. So a progression would be landing mechanics - (stepping off a box) - low amplitude jumping (jump rope) - medium amplitude jumping (box jump sub maximal effort or double unders) - high amplitude jumping (max effort vertical jumps or broad jumps) - depth jumps (landing mechanics plus high amplitude jumping.

Hmmm I kinda like that. I will give it some thought. So do you think squatting could be a progression of landing in a broad sense? Because that's how we teach it indirectly.

This is really for my future self to reference, and if Brian happens to stumble on this article again. But I also came up with a pretty good hierarchy for the top level Tactical-based Movements.

1. Individual skills - these are movements that are signature of a sport and come in the form of chest pass, swinging a bat, a football throw, a baseball throw, slap shot. If we did a pyramid, these would be the bottom layer.

2. Anticipation/reaction drills - this level takes the individual skills and adds a reaction or anticipation aspect to it. For example: Jump to the Ball drill, throwing routes, or a drill that made an outfielder decide whether to hit the cut-off or throw home.

3. Strategy/situations - this involves an entire team usually and is more emphatic on the execution of a play or set than the technique of the skills being performed. These also involve an almost infinite number of reaction components that could come into play. This level would include a motion offense, 7-on-7 scrimmage, or gameplan for pitching to the best hitter.

From my experience, most of the coaches I know spend a majority of the time with #3 because of various reasons. But they often overlook the first two layers. In order to have a play set up for a kid to get a wide-open shot, he has to actually have the skill to shoot. Then, assuming he has that ability, he may have to make a read or decision about where to cut based on where the defense is at. This can be simplified and worked on in the 2nd level.